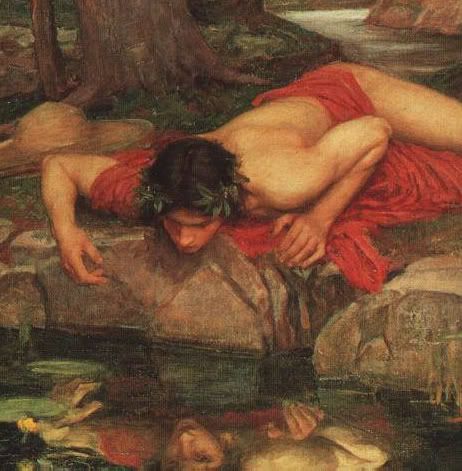

In Greek mythology, Narcissus was a beautiful boy who was promised a long life if he would do one thing--that he would not recognize himself. However, one day he saw his reflection in a spring, fell in love with it, and pined away to death. The myth serves as a lesson to us all, that self-esteem can get out of hand--it can even destroy. The Greeks, in their wisdom, called it hubris, and were fully aware of the excessive pride that led to error and disaster. The lesson they taught is clear--that self-idolatry is the first step toward error on that road to self-destruction. In summary, Self, or ego, is the core human problem.

In Greek mythology, Narcissus was a beautiful boy who was promised a long life if he would do one thing--that he would not recognize himself. However, one day he saw his reflection in a spring, fell in love with it, and pined away to death. The myth serves as a lesson to us all, that self-esteem can get out of hand--it can even destroy. The Greeks, in their wisdom, called it hubris, and were fully aware of the excessive pride that led to error and disaster. The lesson they taught is clear--that self-idolatry is the first step toward error on that road to self-destruction. In summary, Self, or ego, is the core human problem.Indeed, the prohibition against self-love has been a core principle of civilization. It is the foundation of religious and secular culture, and has been institutionalized into the fabric of morality and law.

We in the West are taught from an early age that it was the pride of Adam and Eve, the desire to "be as gods, knowing good and evil," that brought about the Fall. Later in our schooling we read of Milton's Satan, God's chosen angel in Paradise Lost, who is moved by pride to rebel against Heaven. Indeed, he proudly and tragically states, it is better to "rule in Hell" in all the ignominious glory of his pride, "...than serve in Heaven." In the Far East, both Hindu, Buddhist, Confucian, Muslim, and Taoist moral systems hinge on the denial of the Self on the Way, or Path to salvation.

It is without question that all the wisdom of the ages, in both West and East, teaches us this fundamental truth: that self-esteem is not the remedy for--it is the cause of human suffering. And so I ask, shouldn't we then be teaching our students that that the road to happiness is selflessness? Why is it that we do the exact opposite, and instead base our pedagogy on how we can best nurture "feel-good" classrooms? Aren't we doing actual damage to our students? Aren't we, paradoxically, denying our students the most valuable of academic virtues, humility?

I make the bold charge that, out of the fear of offending the sacred Self, we enable a blind narcissism that has eaten away at the fabric of our educational institutions. One might ask, "But how can that be? Don't we serve the academic interests of our fragile students by making sure that they feel good about themselves?" I answer, "No." What is more important than feeling good is doing well. And the road to doing well is defined by the noble act of selfless struggle.

If it were the case that high self-esteem was the essential virtue of the good man, then historically, we would not have seen the most monstrous of acts performed upon the human race by men with the highest self-esteem. Ironically, but fittingly, the the noblest of historic acts have been performed by those with little or no self-esteem at all.

In truth, the absense of self-esteem, not its presence, is the core strength of those who would save the world: people with names like Jesus, Gotama, Gandhi, Mother Theresa, the Dalai Lama. Does it not make us pause, does it not ennoble us, when we read and speak their names? And are we not pained to recite the almost unspeakable names of history's cruellest and most prideful men: Hitler, Stalin, Mao, Pol Pot, Kim Jung Il, Saddam Hussein?

But what do we teachers do? We teach our students to emulate Narcissus, to celebrate the self, to adoringly embrace the self. We teach our students to selfishly identify with culture, race, ethnicity and gender, all principles of division, not union. Indeed, we teach them to adore themselves. The result? Narcissism, with its self-destructive focus on the ego. How can this, in any way, be good?

So therefore, we have it all wrong when we teach our students self-love. What good can come from this Pride Culture of ours, where we openly "celebrate diversity," and cultivate concepts of division and self-identification? Ironically, tragically, it has become politically correct to have pride. It is politically correct, in the name of "social justice" and "multiculturalism" to have ethnic pride, nationalistic pride, gender pride--even racial pride--which nurtures the very vices that are the source of intolerance, wars, and human suffering.

And what does this do but Balkanize the mind? What does this do but divide the self in search of oneness? And if this celebration is nothing but narcissistic ethnocentrism, nationalism, sexism, and racism, why then do we encourage it? Haven't we learned yet that centralizing the self at the expense of others only leads to more division, not less? Haven't we yet learned that if we're all celebrating what we are, there's little left to celebrate in others? I ask, if everyone is different, what do we share? If everything is good, is nothing evil? If everything is permitted, what place is there for shame?

I propose an alternative view. I propose that we should celebrate what we share in common; our common humanity and values. I propose that we establish "Other-esteem" as our core virtue.